A CLOSED LOOP

PICTURES IN ROOMS

FIELD WORK

ARRIVE BY MAGIC

2020/12/15

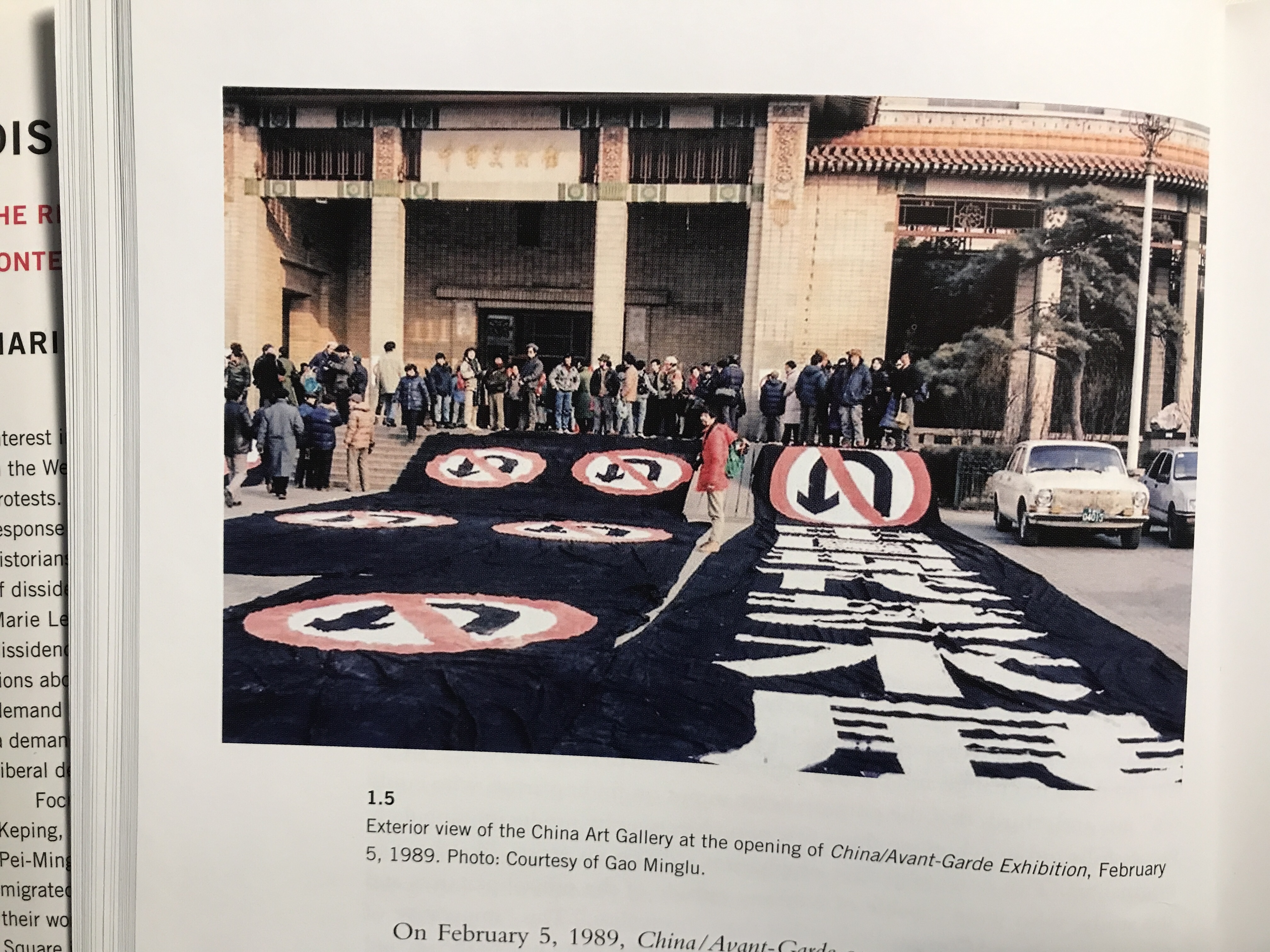

Dissidence: The Rise Of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West by Marie Leduc serves as a reminder of my own subject position which inhibits me in two ways--knowing that my words and actions are under potential surveillance, and knowing that any expressions of criticism might be subject to valorization, with the side effect of misaligned if not patronizing empathy. There's a tension between the two since one endangers the other. Being recognized as a dissident comes with its own set of repercussions which I have been taught to avoid as part of the reality of growing up in my home country where harmony and stability had to be maintained.

Few of the artists mentioned in the book engaged directly in Chinese politics, yet none the less they were valorized as dissident artists for producing ideas under a condition that posed certain challenges and restrictions. And in place of explicit political expressions, an up-to-date understanding of the contemporary art's production in the West seemed to be key among those who were able to garner the most success, although there still needed to be visible indicators of an artwork’s "cultural specificity" (a.k.a "Chinese-ness"). So whether by will or circumstance, these selections of Chinese contemporary art ended up reinforcing the bond between artistic production and liberal democracy in Western culture.

The intricate part is that the countries that claimed the ideal of liberal democracy also welded the power to both valorize (and therefore endanger) and shelter individual artists. The three Chinese artists along with art historian Fei Dawei who participated in Les Magiciens de la Terre in 1989 were offered asylum by the French government. It was one of the few cases the where the logic of such patronage (in symbolic capital) manifested in its completion. The reinforced ideal of liberal democracy actually extended its power to resolve the process which it had initiated. But how often does this scenario happen? Does it depend on the frequency of which liberal democracy feels the need to renew itself? And what exactly is the capacity if the process operates on a case by case basis? The largely symbolic guesture will likely fail to meet the demand of a community, just looking at the tightening of immigration policies across America and Europe.

The Venice Biennale chapter was interesting because not only does it further revealed the extend of which Chinese contemporary art depended on Western value systems and methodologies, being literally absorbed into the Italian pavilion in 1999, but it also presented a staggering timeline showing that it wasn't until 2004 did China appear to "get the memo" and stage a "contemporary" exhibition. The reluctance could be understood as an ongoing effort for China to solidify a national identity, as well as to demonstrate its power in occasions of cultural exchange (eg. the official selection of Chinese films for Oscar nominations). Regardless of my rationalization, the massive time gap in the development of contemporary art was impactful to witness. As early as 1948, the Americans already had success in cultural export at the Venice Biennale with the introduction of abstract expressionism--something that the traditional arts and craft had failed to do for China.

Turning to the landscape right now, political dissidence doesn't feel quite as monolithic of a criterion when it comes to the circulation of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West, despite it still remaining a useful and integral device. The heterogeneity inherent to my identity and its displacement will always retain the potential of being heightened politically and threatening my agency as an individual. Maybe that kind of awareness is at the root of what was inhibiting me of being overtly critical of the Chinese educational system, as I was trying to preserve the agency of my lived experience. And the effect of the self-censoring and self preservation was an atmosphere of linguistic fogginess and ambiguity that was turned into melancholy.

![]()

Few of the artists mentioned in the book engaged directly in Chinese politics, yet none the less they were valorized as dissident artists for producing ideas under a condition that posed certain challenges and restrictions. And in place of explicit political expressions, an up-to-date understanding of the contemporary art's production in the West seemed to be key among those who were able to garner the most success, although there still needed to be visible indicators of an artwork’s "cultural specificity" (a.k.a "Chinese-ness"). So whether by will or circumstance, these selections of Chinese contemporary art ended up reinforcing the bond between artistic production and liberal democracy in Western culture.

The intricate part is that the countries that claimed the ideal of liberal democracy also welded the power to both valorize (and therefore endanger) and shelter individual artists. The three Chinese artists along with art historian Fei Dawei who participated in Les Magiciens de la Terre in 1989 were offered asylum by the French government. It was one of the few cases the where the logic of such patronage (in symbolic capital) manifested in its completion. The reinforced ideal of liberal democracy actually extended its power to resolve the process which it had initiated. But how often does this scenario happen? Does it depend on the frequency of which liberal democracy feels the need to renew itself? And what exactly is the capacity if the process operates on a case by case basis? The largely symbolic guesture will likely fail to meet the demand of a community, just looking at the tightening of immigration policies across America and Europe.

The Venice Biennale chapter was interesting because not only does it further revealed the extend of which Chinese contemporary art depended on Western value systems and methodologies, being literally absorbed into the Italian pavilion in 1999, but it also presented a staggering timeline showing that it wasn't until 2004 did China appear to "get the memo" and stage a "contemporary" exhibition. The reluctance could be understood as an ongoing effort for China to solidify a national identity, as well as to demonstrate its power in occasions of cultural exchange (eg. the official selection of Chinese films for Oscar nominations). Regardless of my rationalization, the massive time gap in the development of contemporary art was impactful to witness. As early as 1948, the Americans already had success in cultural export at the Venice Biennale with the introduction of abstract expressionism--something that the traditional arts and craft had failed to do for China.

Turning to the landscape right now, political dissidence doesn't feel quite as monolithic of a criterion when it comes to the circulation of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West, despite it still remaining a useful and integral device. The heterogeneity inherent to my identity and its displacement will always retain the potential of being heightened politically and threatening my agency as an individual. Maybe that kind of awareness is at the root of what was inhibiting me of being overtly critical of the Chinese educational system, as I was trying to preserve the agency of my lived experience. And the effect of the self-censoring and self preservation was an atmosphere of linguistic fogginess and ambiguity that was turned into melancholy.